A Love With No Tomorrow: How George Jackson and Angela Davis Inspired My Novel

From Soledad to Subtext: Love Letters That Lit a Fire

This Black August, I am thinking of George Jackson. His quote opens Book One of my novel. It’s a line for a letter he wrote in 1970 to the woman he loved at the time, a woman we all know as Angela Davis.

In the letter, he says, “It's crazy, all women, even the very phenomenal, want at least a promise of brighter days, bright tomorrows. I have no tomorrows at all.”

This line broke me. Perhaps because it speaks of doom, of someone who doesn’t dare dream of love or anything at all because as an incarcerated Black male who was repeatedly denied parole, repeatedly treated as a threat and repeatedly sent to solitary confinement, he knew there was no promise of freedom for him or his fellow inmates.

But mostly, it broke me because he had evolved into a brilliant, self-taught Marxist-Leninist theorist who penned Soledad Brothers, taught political education to fellow inmates, inspired Black Revolutionaries around the world with his plight and his manifesto including Huey P. Newton himself, and co-founded the Black Guerilla Family, and he knew he could not offer any white picket fence dreams to anyone, not even a revolutionary woman like Angela Davis.

No tomorrows at all. Imagine not enternaining dreams of the future. How could we expect this of a man who was incarcerated at the age of 17 for stealing $70 from a gas station and being sent to life for such a petty crime. Imagine not entertaining hope — how could he? The more revered he became, the more the warden and prison guards saw him as dangerous to the status quo, someone who had to be made an example in order to deter others from dreaming, from wanting liberation for all Black people?

This line was the inspiration for the title of my novel, Kingdom of No Tomorrow, and the emotional and political axis for this book. It is a story about love in the margins, yes, a story about Black love, but specifically love that is doomed so long as it endeavors to fight against marginalization. Very much like Melvin and Nettie, characters in my novel, living a story that I wanted to read more about in real time through fiction. If you do ask me why I wrote this novel, in part, this was why.

The Fire Between Them

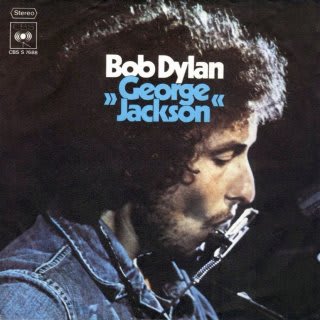

George Jackson was not only a revolutionary and political prisoner—he was a writer whose words pulsed with urgency, rage, and raw love. He educated himself while in prison to become a most brilliant thinker who later inspired songs by bards the likes of Boby Dylan. See for yourself in the lyrics from the song George Jackson:

Prison guards, they cursed him

As they watched him from above

But they were frightened of his power

They were scared of his love

Lord, Lord

So they cut George Jackson down

Lord, Lord

They laid him in the ground.

From his cell, George Jackson penned Soledad Brother, a searing collection of letters that reveal a man sharpened by state violence, yet softened by the act of writing. His mind was militant, but his language—especially in private letters—was intimate, vulnerable, and poetic. He also wrote Blood in My Eye, a book of political philosophy which he finished just days before his death — he was gunned down while running away during an attempted prison break.

Angela Davis, at the time, was already a radical icon in the making: a brilliant philosopher, a Communist, and an outspoken critic of the prison-industrial complex. She was teaching at UCLA, organizing outside prison walls, and, eventually, fighting her own legal battle.

But beneath the headlines and the buzz of the era, there was something unspoken, even secret: a deep, electric love between two people who didn’t have the luxury of candlelit dinners or Sunday mornings, only letters. Much like Melvin and Nettie, they didn’t go out on dates. Their love was spent writing, reading, studying and engaging in activisim.

Their correspondence was an act of rebellion and courtship. In their letter exchages, they built a sanctuary. Davis once said, “I loved him deeply... we loved each other through struggle.” Their words were laced with love, but also with brutal honesty, with harsh and profound meditations on class struggle, on anti-racist thought. And they also whispered desire (those letters had to be read aloud during Angela Davis’ trial - imagine having to hear your own private mail read in public).

History was eager to erase them out of consciousness, but in writing each other, George and Angela wrote themselves into each other’s futures, even knowing they might never share one. And if you know anything about me by now, you know this is what I live for. Rewriting our erased selves back into history is exactly my jam.

Romance as resistance

And maybe that’s what makes their bond so electrifying to me. It wasn’t rooted in fantasy or luxury. It was forged in absolute fire, in a love one couldn’t put in a box or in the can. It’s not celebrities caught in a love affair that make us roll our eyes. This is real love despite the harshest of conditions.

For me, George and Angela are proof that revolution can be tender at times, and that even in the bleakest conditions, love still rises up, unbowed. So when someone asked me once if the love between Melvin and Nettie was absolutely necessary, my answer is yes. It was, it is, it always will be, and I make no apologies for how I see love show up in my writing. These stories are the way I want to capture romance and tenderness: through struggle.

And when I speak of struggle, I don’t mean the Hallmark Channel notion of conflict where a female protagonist fights tooth and nail to run a flower shop against a dashing, muscular rival before they finally fall in love right on time for Christmas.

I’m speaking of this: never seeing your love in person, knowing your love’s life is always on the line, always endangered, definitely threatened, definitely demonized. I’m speaking of watching your love story, your bodies, your dreams slowly erased out of existence. I’m speaking of marching and protesting and challenging empire all the time despite its efforts to crush your innate right to love (see image above - Angela Davis and Gerge Jackson’s brother Jonathan protesting in favor of the Soledad Brothers, just months before Jonathan is himself assassinated in the Marin County Courthouse Rebellion in which he attempted to demand the release of his brother).

As much as I realize and understand the need for Black love stories that are not rooted in trauma, I want to delve into the love that endures and survives beyond the pitfalls of revolution and conflict. I’m okay staying on this hill a while because in honoring and remembering those stories, we remember that there come times when love and joy can often be luxuries and become impermissible to us.

Love as legacy

I’m not saying Melvin and Nettie are exactly the same as George Jackson and Angela Davis.

I am meaning to say, however, that George and Angela’s love inspired me. And without spoiling the novel if you haven’t read it yet, I will admit that you will encounter moments in the Melvin and Nettie romance that echoes the past.

Instead of going to the movies, or going out to dance, or going out to restaurants (Melvin and Nettie do eat out once but there is a political catalyst for this), they read books together. Melvin leaves Nettie poetry collections by Nikki Giovanni. In the same way, George and Angela’s letters speak of the theorists and philosophies they study, including Lenin, Marx, Mao, Che, Fanon, Nkrumah to name a few. Sometimes I even wonder about the force of nature this couple could have been had they not been separated by prison bars and other life circumstances.

In that same letter, here is what George Jackson wrote to Angela Davis:

“You probably hear these devotions all day, and with your incentive factors they're probably all sincere devotions. Let me heap mine on you (with these pitiful little strokes of the pen) for the last time (unless seized by ungovernable impulse) with a statement made at the risk of seeming immodest; but I am modest and I hope that it is righteous for me to feel that — no one, and much more meaningful no black, wherever the hurricane has washed up his broken body, no one at all, can love like I.”

That last line, am I right?

George Jackson didn’t believe he had a tomorrow. In a world that sought to crush him, he wrote himself a future—through letters, through revolution, through love. And Angela Davis, in loving him back, showed us that tenderness could exist within the teeth of struggle, that even the most radical political fire could burn with intimacy. From Angela’s letter to George Jackson,

“This has been a week I didn’t think I would be able to survive. Not for many months have I been so depressed … so many other things around me have crumbled, but I don’t think this is an appropriate time to bother you with all the details of my troubles. You’re the only one who can bring me out of states like this … there’s this huge thing between us … I don’t love you less — that’s something beyond my control. But I just can’t go on like this. Please be kind to me and let me know immediately what this whole thing is all about.”

It hurts my heart to read this longing and sorrow.

Yet, their story is not a footnote in the fight for Black liberation. It is a blueprint. A reminder that movements are made of people—flesh, blood, dreams, heartbreak. In their words, I found the pulse of Kingdom of No Tomorrow—a novel not just about history, but about the deep emotional truths that history often hides.

George Jackson died in San Quentin. You can find out more about the absurd description of his death by the guards, which sounds just as much as a cover up as the death of Fred Hampton. The evidence clearly tells us a story the authorities will not, that he was gunned down while running away during a prison break attempt. For years until now, questions linger around his death.

Inspiration always comes to me in the strangest places and from the most uncertain sources, much like the way revolutionary triumph can bloom like flowers in the most uncomfortable cracks. Sometimes, it arrives in the tragic, the unfinished, the yearning.

From George Jackson and Angela Davis, I learned that love can be a form of resistance, and that even when tomorrow is denied, we can still write toward it. At least that’s what we writers do.

Meanwhile, I continue to think of George Jackson, particularly during Black August. I think of his courage, his heart, and the lessons he left behind for us to sharpen our outlook on the actual world we have been dealt. Bob Dylan would probably confirm.

Sometimes I think this whole world

Is one big prison yard

Some of us are prisoners

The rest of us are guards

Lord, Lord

They cut George Jackson down

Lord, Lord

They laid him in the ground

Additional readings:

Extreme Remedies by Max Nelson for the Paris Review

Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson

The 50th Anniversary of the August 7th Marin County Courthouse Rebellion

Any additional suggestions or any comments? Drop them in the comments and tell me how revolutionary love inspires you.

And if you liked learning about George Jackson and Angela Davis, please share and subscribe!